Famagusta (Mağusa) – 18th October

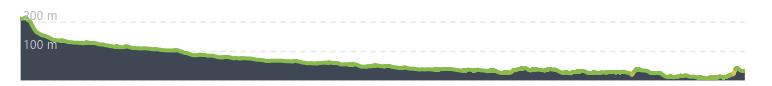

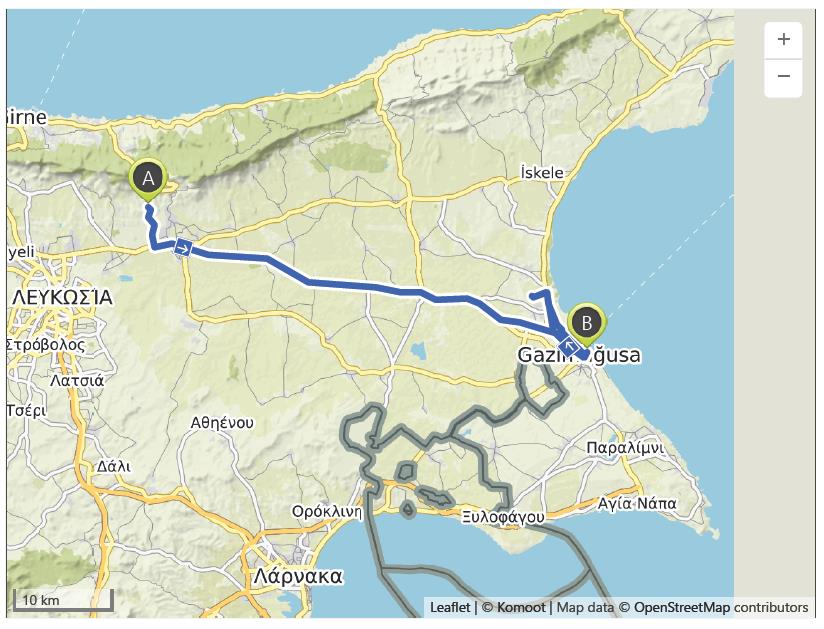

Distance: 121.2 km – Elevation +520 m -480 m

Weather: Sunny. Temperature: High 29 degrees

After another good night’s sleep, I rose at 8.00 am and joined Nelly for breakfast. I spoke to the staff of the hostel about getting to Famagusta and was told we needed to book seats on a minibus that stops about a 10 minute walk from the hotel. The earliest bus with seats available was 12 noon, and as Nelly’s ferry back to the mainland did not depart until 10.00 pm it left plenty of time to visit Famagusta and the Abbey.

The journey to Famagusta took us over the Kyrenia Mountains with spectacular views of the mountain peaks, including the Pentadáktylos mountain. The mountains were serenely beautiful as they rose majestically into the brilliant blue sky as if trying to reach the puffy white clouds floating above. From the mountain peaks, the road passed through the villages of Arapköy and Minareliköy as it descended to the agricultural heartland of Cyprus, the Mesaoria plain. We arrived at the Itimat bus station in Famagusta at just past noon and after arranging seats for our return journey we stopped for a light lunch in a nearby cafe before taking a taxi to the Monastery.

Famagusta’s origins stem from a late 3rd century earthquake that destroyed the ancient city of Salamis. Following the earthquake, a new village, called Arsinoë, started to grow 6 kilometres south of Salamis. Salamis was rebuilt by emperor Constantine and renamed Constantia but was destroyed by the Arab invasions of the 7th century subsequently most of its residents moved to Arsinoë. It is claimed that the Lusignan rulers changed the name to Famagusta in the medieval period. Since 1571, Famagusta has been called Mağusa by the Ottoman and Turkish Cypriots.

The taxi took us out of town past the rather dark and austere Zafer Anıtı (Victory Monument) on Yirmi Sekiz Ocak Meydani (Twenty-eight January Square). It was built by the Turkish military following their 1974 invasion designed to depict the struggle of the Turkish-Cypriots of Famagusta through the years and remaining victorious in the end. It is topped by a massive head of Kemal Atatürk and has the flags of Turkey and North Cyprus in front. We continued along the Salamis road and just before reaching the site of the ancient city of Salamis we turned towards St Barnabas Abbey, passing the site of the Royal Tombs complex where we stopped to view tomb 50 or St Catherine’s Prison.

“St Catherine was a royal princess, the daughter of King Constant of Cyprus, born around 287 AD. The Roman emperor at the time was Diocletian, who was known for his cruel persecution of Christians. When Constant was transferred to Alexandria to rule over Egypt, his brother became administrator of Cyprus. King Constant died soon after his arrival in Alexandria, and his daughter was sent back to her uncle in Cyprus.

When her uncle learned that she had become a Christian, he tried to convert her back to the pagan religion. Catherine was unyielding, and proclaimed her faith with such determination, that her uncle was forced to take harsh measures against her. Fearing that the emperor would put him to death for protecting her, her uncle imprisoned her first at Salamis, then at Paphos, before sending her to Alexandria.

The ruler of Alexandria at the time was Maxentius, son of the emperor Diocletian, and he was as ruthless as his father. He also tried to get her to change her faith, without success, torturing her and throwing her into prison. He asked 50 philosophers and orators to convince Catherine to return to the religion of her fathers. She countered their arguments to such an extent that she converted them to Christianity. This infuriated Maxentius, who ordered that the philosophers be burned at the stake.

It is also said that when Maxentius was away from Alexandria, his queen, followed by 200 officers and men visited Catherine in prison to convince her to relent. the soldiers were so impressed by Catherine’s convincing defense that they were converted to Christianity and baptised. When Maxentius heard of this, he had them all beheaded.

He finally ordered that Catherine should be severely beaten and tied to a rolling spiked wheel. Ever wondered where the firework got its name? Although she survived this torture, she was beheaded in 307.” –

(Text from: http://www.whatsonnorthcyprus.com/interest/famagusta/salamis/catherine.htm)

“The Monastery of St. Barnabas is at the opposite side of the Salamis-Famagusta road, by the Royal Tombs. You can easily tell it by its two fairly large domes. It was built to commemorate the foremost saint of Cyprus, whose life was so intertwined with the spread of the Christian message in the years immediately following the death of Christ.

Barnabas was a native of the ancient city Salamis, and was a Jew, though his family had been settled for some time in Cyprus. His real name was in fact Joses, or Joseph; Barnabas was the name given to him by the early Christian apostles because he was recognised as `a son of Prophecy’, or as Luke puts it `a son of consolation’. There is no contradiction here. Luke is merely emphasizing that one of the great historic functions of prophecy was to console the believer and keep him in the faith.

He was reputed to be an inspired teacher of Christianity, but more than that he played a very great role in the development of early Christianity. He was also the man to acknowledge that Paul’s conversion to Christianity was absolutely sincere, and above all, he recognised the genius of Paul, whom he introduced to the Christian fellowship in Jerusalem. When Barnabas was later sent to Antioch to supervise the work of the early Church there, he had Paul as his assistant. Later still, of course, he undertook his great missionary journey with Paul, visiting among other places, his own country of Cyprus.

Finally, of course, we know certainly that Paul and Barnabas had a strong difference of opinion about Barnabas’ nephew, John Mark, and the two friends parted company. Paul wrote later that the rift was healed but by that time Barnabas was probably already back in Cyprus.

The monastery which bears Barnabas’ name was originally built in the last part of the fifth century, to commemorate the discovery of his body, and the dignity and the seniority it brought to the early Christian Church of Cyprus. Parts of the early building have been preserved in the more recent church which was built by Archbishop Philotheos in 1756. The money for the purchase of the land on which the monastery was built, is supposed to have been provided by the Byzantine Emperor at the time Barnabas’ body was found.

When you look carefully at the church you will notice the traces of the original fifth century building and also places it seems to have been enlarged and changed, probably in the very late medieval period. But in the main it is fairly conventional Greek Orthodox architecture of the eighteen century.

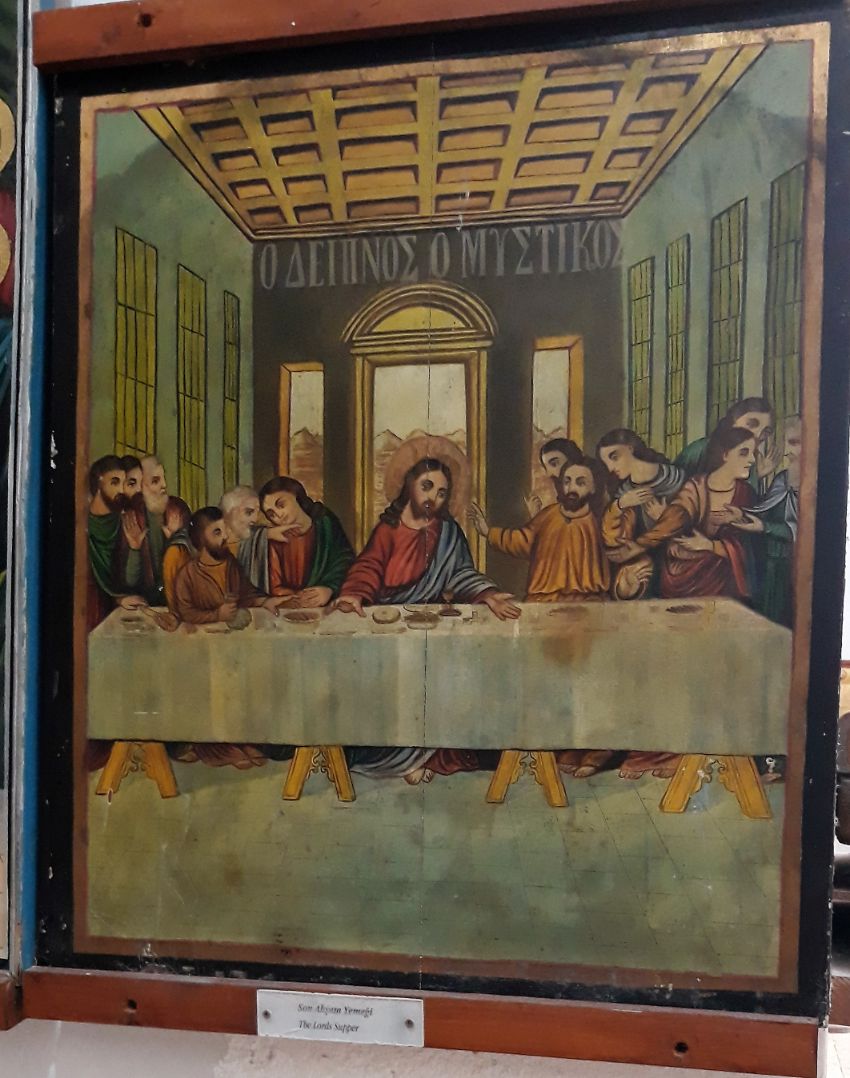

On one of the walls, the story of how Barnabas’ body was shown to the Archbishop in a dream, is rendered in small pictures. These were done in the present century, but some of the icons and statues are a good deal older.

On another wall, somewhat incongruously, hang wax replicas of limbs in a gesture of gratitude for the ailing limbs which the Apostle Barnabas is supposed to have miraculously cured. Close by, the image of st. Heraklion stares at you from every angle you choose. All these items, ancient and modern, have been very well looked after and are shown with great pride by the curator of the church.

The marble columns supporting the domes are conspicuous and rather spectacular. It is impossible to be certain, but these may well have come from Salamis. In one sense, the little rock tomb in which Barnabas is supposed to have been found gives the authentic flavour of the Christian evangelist and martyr much more effectively.

The church of St Barnabas is exactly as it was when its last three monks left it in 1976. The church apparatus; pulpits, wooden lectern, and pews are still in place. It houses a rich collection of painted and gilt icons mostly dating from the 18th century.

The carved blocks and capital blocks in the garden and cloister courtyard come from Salamis. The black basalt grinding mill comes from Enkomi.

The cloister of the monastery has recently been restored and at present serves as the archaeological museum. This section houses an exquisite collection of ancient pottery displayed chronologically, representing the changes in morphology and decoration of pottery in Cyprus from the Neolithic to the Roman times. The rest of the collection covers bronze and marble art objects.” Text from: http://www.cypnet.co.uk/ncyprus/city/famagusta/stbarnabas/index.html

After the visit to the Monastery, we returned to Famagusta to visit the old walled city, which since the 12th century has been in the hands of the Lusignans (1192-1489), Venetians (1489-1571), Ottomans (1571-1878), and British (1878-1960).

It was during the Lusignan period that Famagusta started to grow and the citadel and fort were built, it was during this time that the cathedral of St. Nicholas was built. The existing walled city with its two gates, the Sea Gate (Porta del Mare), and Land Gate (Ravelin) were constructed by the Venetians. After the Ottomans conquered the city in 1571, the cathedral of St.Nicholas was converted to the Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque and it was during this time that emigration from Anatolia changed the population from predominately Christian to Muslim.

In 1878, the Ottomans leased the island to the British, and in 1910 it became a true colony of the British Empire. The population outside the city walls grew significantly and a new suburb, Varosha, was created. The Greek Cypriot residents of Varosha left during the Turkish invasion in 1974 and it has remained fenced off and uninhabited since that time.

We entered the walled city through the Land Gate and walked through the narrow streets of shops and cafes and came to the historic Namik Kemal Meydani and the remains of the Venetian Royal Palace. We sat beneath the oldest tree on Cyprus, the Cumbez Tree, a tropical fig tree claimed to be over 700 years of age. We visited the magnificent Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque converted from the St.Nicholas cathedral first consecrated in 1328. Its Gothic architecture is similar to Reims Cathedral in which I had visited earlier in my pilgrimage to Jerusalem. We also visited the Sinan Pasha Mosque another Ottoman conversion from the Christian Church of Saints Peter and Paul built around 1360.

Our return bus left at 6.00 pm. It was an extraordinary return journey to Kyrenia in an ancient crowded bus with broken seats and seemingly no suspension! From the hostel, I walked with Nelly to the ferry terminal where we said our goodbyes and I returned on foot to the hostel to prepare myself for the continuing journey to Jerusalem.